OECD Tax Project Could Affect Government Credits From R&D to Low-Income Housing

Most of the discussion surrounding the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) five-year-old international tax project has focused on difficulties with taxation in the digital economy, as well as tax avoidance by corporations in the tech sphere through valuable intangible assets.

But increasingly, it is clear that the 15% global minimum tax which is a large part of its final agreement, signed onto by nearly 140 countries, will also have profound implications on how every government uses incentives and tax credits to boost their economy.

The final plan, should it be implemented, won’t just affect how much countries spend through their tax codes to aid businesses. It will likely also influence the types of incentives that governments can use—requiring all tax practitioners and multinational corporations to review how those incentives affect their tax structures and operations.

It also may be more far-reaching than many of the participants in the project realized when they first signed up.

Collateral damage?

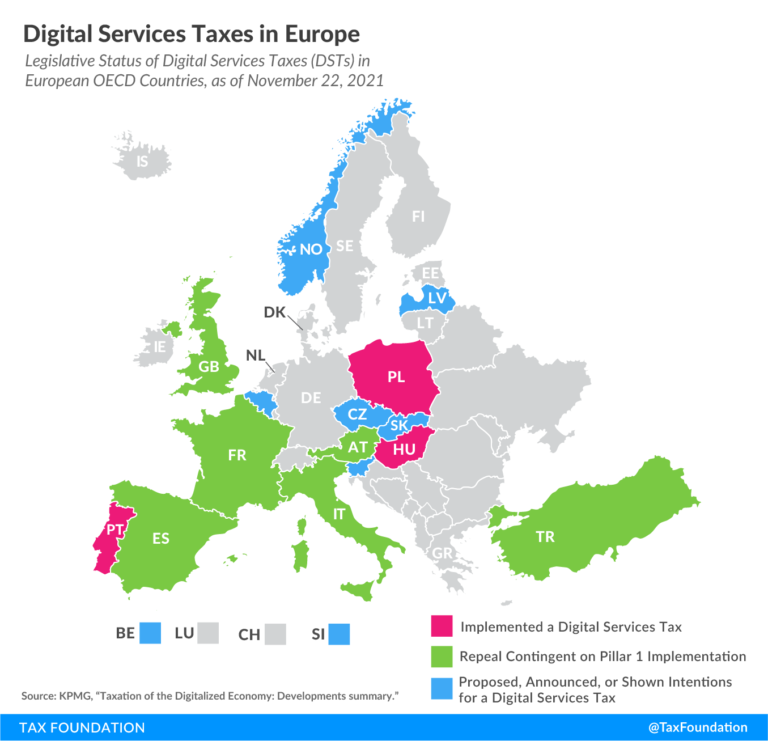

The negotiations began in 2017, as many European countries explored digital services taxes, targeted at revenue from online activities such as e-commerce and data collection. The G-20 asked the OECD, which sets global tax policy, to reach a consensus solution on how to update the tax rules to address the digital economy.

Since then, the project’s scope has expanded to include many other aspects of the global tax system. And in recent days, OECD officials have indicated that changing the nature of government tax incentives isn’t an unintended byproduct–it’s something they’ve long wanted to be a core part of the effort.

“We have a very strong view that if governments are going to promote innovation, there are good ways of doing it and bad ways of doing it,” said John Peterson, a senior tax official at the OECD, during a June conference co-sponsored by the OECD and the U.S. Council of International Business, held in Washington, D.C.

“And the good ways of doing it involve providing financial support up-front, and that is not somehow contingent on future profit returns,” he added.

This is reflected in how the OECD’s global minimum tax considers refundable and non-refundable tax credits, as part of the new calculation of income that determines whether a company is taxed above the 15% rate for the global minimum tax.

“So the line that was drawn in the sand was, in one sense, a very deliberate one,” Peterson said.

YOUR CPE CONFERENCE IS WAITING

Don’t wait to book your 2022 CPE Conference. Register for your location today.

Nixing Nonrefundable Credits

Under the OECD plan, nonrefundable credits are considered a reduction in taxes, lowering a company’s effective tax rate and increasing the chances it will fall under the 15% minimum rate. In that case, the countries where that company is present will tax it on the difference.

For most refundable credits, the calculation will consider them as income, not a tax reduction. By increasing the company’s taxable income, it will change its effective tax rate–but to a smaller degree than non-refundable credits would.

In simplest terms, the OECD calculation doesn’t really consider a refundable tax credit, which can be immediately turned into cash, to be a tax credit at all. It looks at it as a form of direct support, just like a subsidy.

This could affect U.S. companies which use non-refundable credits, such as the research & development credit, on domestic income. The U.S. doesn’t plan to tax its own companies more, but the agreement includes an enforcement mechanism, the UTPR, which other countries can use on foreign companies doing business in their jurisdiction. The UTPR would apply when a foreign company has income that is taxed below the 15% rate anywhere else it is present, including its home jurisdiction. This is meant to prevent countries from attracting businesses by simply refusing to follow the agreement. (It’s just “UTPR”–the acronym once stood for the “under-taxed payment rule,” but the OECD dropped that meaning as the structure evolved.)

If a U.S. company’s use of tax credits lowers its domestic effective tax rate below 15%–after taking into account the “substance-based carveout,” an exemption for tangible assets and payroll, which may cover many U.S. taxpayers–the UTPR could then apply in other jurisdictions. This would happen even if the U.S. fully implements the OECD proposals, which at this point appears unlikely. Should the U.S. fail to comply with the new OECD standards, the tax consequences for U.S. companies in this situation could be larger.

Congressional Blowback

The possibility that the plan would increase foreign taxation of U.S. multinationals–negating preferences enacted by Congress, no less–has ignited a political firestorm on this side of the Atlantic. While it was always part of the design, there was little discussion of the issue before the agreement was reached in July 2021, and it seems to have caught many off-guard.

Administration officials say they’re working with both the OECD and Congress to protect those tax incentives, although they’ve conceded that a change in the law may be necessary to keep the value of the R&D credit. OECD officials have said that the plan simply follows basic accounting principles, which account for tax credits the same way. But Peterson’s comments confirm that it’s not so much a bug as a feature in the plan’s design.

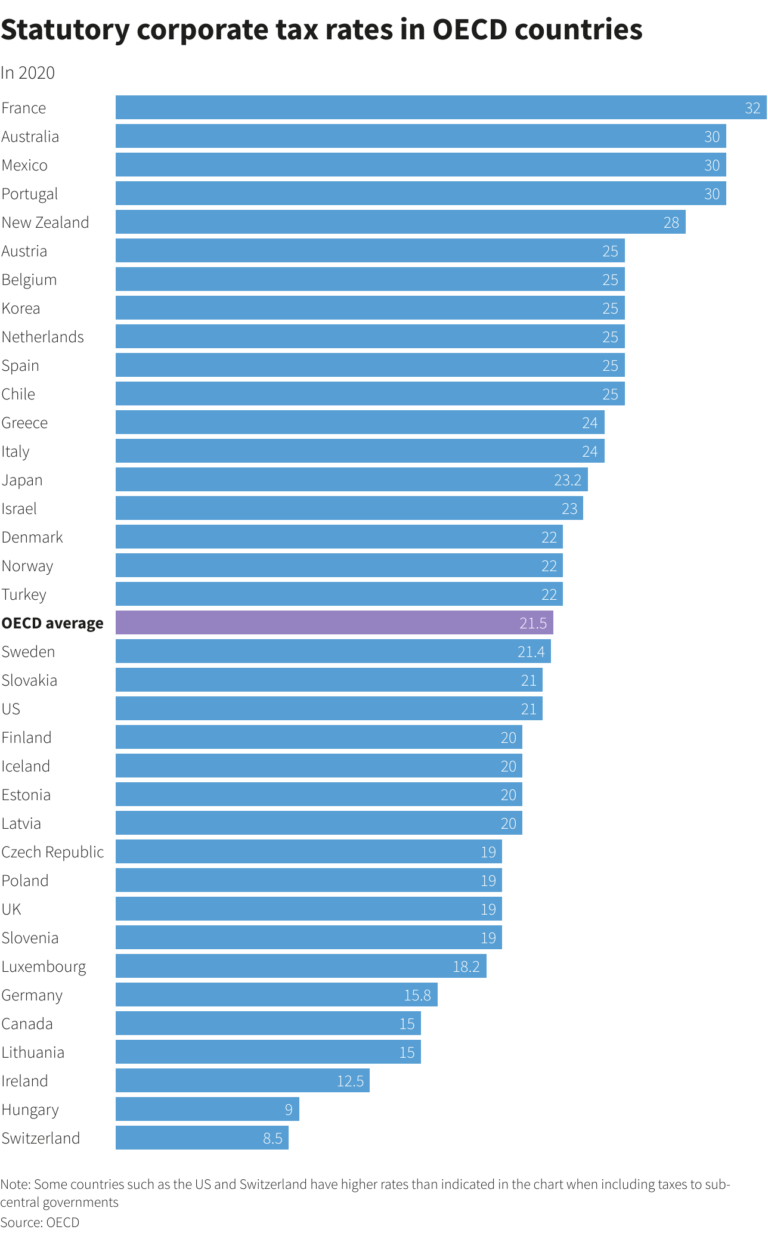

After all, supporters of the plan, especially in the Biden administration, claim that it will end the global “race to the bottom,” or countries’ efforts to lower taxes to attract investment. One of the primary ways that nations participate in that race is through tax incentives.

But they also use tax incentives to support green energy projects, spending on housing and other social programs, and whatever other causes governments find to be worthwhile. Many simply assumed that exceptions would be made–but for the OECD to create a list of acceptable credits, specific to various countries, would be all but impossible.

Wiggle Room

While the project is technically past its design phase, and into the implementation phase, officials have found some ways to fine-tune the rules to accommodate a few of these credits. OECD officials suggested that transferable credits, or those which companies can transfer or sell to another, may be considered refundable even if companies can’t receive a direct refund from the government. Accounting under the “equity method” may protect credits for low-income housing when they involve funding.

Otherwise, countries will likely have to change their tax codes to accommodate these new global norms. This may be easier for some than others–for instance, many developing countries have faced difficulties providing value-added tax refunds, creating overall instability in the tax systems. Those under a cash crunch may not be able to offer up-front credits to taxpayers.

Perhaps, though, this is part of the project’s goal–to force countries to re-examine their tax codes and fine-tune them to provide support in the most optimal and efficient way. That’s a worthy debate–but the debate, so far, seems to have happened behind closed doors.